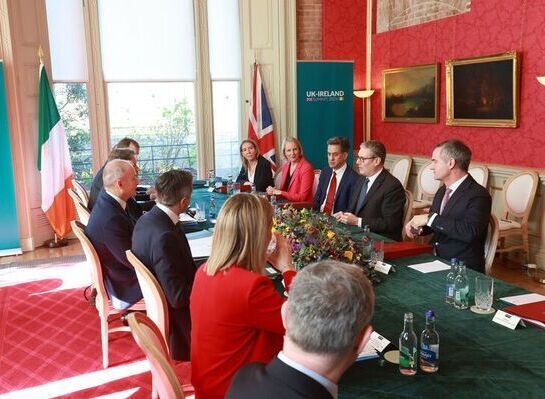

A woman takes a break from gardening to answer a 1940 census enumerator’s questions. U.S. CENSUS BUREAU

By Peter McDermott

A major heritage resource is just a few keystrokes away.

We shouldn’t need a reminder, but the taking of the 2020 U.S. Census is a big one anyway.

The resource is the collective record of the census returns available to the public here and in other Anglophone countries. A recent article mentioned the easily accessible and readable 1901 and 1911 Irish census returns and also cited important American equivalents.

This week, we’ve asked three researchers to introduce the US Census records and to provide some guidance and moral support for the beginner.

Linda Dowling Almeida is an adjunct assistant professor at Glucksman Ireland House, New York University, and author of “Irish Immigrants in New York City, 1945-1995” (Indiana University Press, 2001).

The United States Census is top of mind for many of us as we fill out the forms that are due back to the Census Bureau this fall or work on a family tree that may have become a project during Covid quarantine. As my colleague, Hilary Sweeney shared in the Sept. 3 edition of the Echo, Census documents are treasures waiting to be mined by historians and family researchers alike. They are public documents that anyone can access. The beauty of the census is that it reveals demographic data from a macro level, such as how many women are heads of household in a particular year in New Jersey, to the micro level like the names of people in a specific household in Newark. The caveat on the latter is that individual personal information is only available to the public up to 1940. In the United States regulations require that individual census records be held for 72 years to protect the privacy of the respondents (1950 records will be released in 2022). According to the US Census Bureau, the only way for the 1950 to 2010 records of an individual to be released is by the formal request of the person or his or her heir. The individual census records from 1790 to 1940 available to the rest of us are rich in detail.

For conducting family histories of the early 20th century you can discover not only where your ancestor lived, but nuggets like the names, ages, birthplaces, occupations, and literacy of your ancestors as well as who else might have lived with the family in a particular year. Maybe your great-grandparents had boarders in 1930, maybe they had servants, maybe you knew that, maybe you didn’t, but the census can offer up that information to you with a few clicks on your computer in the privacy of your own home.

When I was conducting research for my study of the 1950s Irish in New York, I spent hours reeling microfilm on spools in the library to study census tracts from the five boroughs and learned that in 1950 Manhattan boasted the largest number of Irish-born, Staten Island, the smallest. Further digging determined the numbers of immigrants living in particular neighborhoods within each borough, their marital status, and whether they sent their children to private or public school and to what grade level. I used that information to construct a profile of the immigrant community that provided some specificity to complementary research from other less numerically detailed sources, including letters, newspapers, and interviews. While losing yourself for hours in the basement of a university or local library is rewarding in itself, the digitized sources currently available from the Census Bureau and National Archives or on sites like Ancestry.com make life ever so much simpler, especially in these days of Covid. The pandemic need not interrupt anybody’s research or the reverie of discovery.

Linda Dowling Almeida of Glucksman Ireland House, New York University.

Tom Myles, of Oakdale, N.Y., has been an active genealogist for more than 20 years. “Several people have told me I could get paid for what I do. My standard reply is, ‘Then it would be work,’” he said in a 2018 Echo interview. “I often voluntarily assist others, friends or other people needing assistance. Perhaps the best ‘payment’ I received was after helping someone who was trying to become a member of the Daughters of the American Revolution. She wrote to me: ‘You’re my hero!’”

I do genealogy research almost every day. Quite often I am looking at a United States Census page. I have viewed decennial US Census pages from 1830 to 1940, and many State censuses. At times the page gives pertinent information and at other times, it can be frustratingly inexact.

It is important to know that unlike the vital records, birth, death, and marriage (BDM), the information on the page is not “official.”

I also have worked for the US Census Bureau for the 2010 and 2020 censuses, so I can say the following with accuracy. The first thing to consider when assessing the information is to consider the census taker. Typically, the census worker was recently out of work. Enough said!

In previous censuses, the census taker went door to door soliciting information. Usually he would encounter one member of the household who would relate to him the name, age, birthplace, occupation, and other required information. The respondent may not know all the information requested, but it’s the census taker’s role to record the information as given

The USA is in good part an immigrant nation. When the census enumerator encounters a respondent from another country, there may be a language barrier, or even the respondent’s accent may be difficult to understand. Couple that with the fact that many immigrants anglicize a name just to fit in. From one census to the next Heinrich becomes Henry, Giuseppe becomes Joseph, and so on.

Because much of this information can be personal and embarrassing to some, answers may not be truthful. Out of wedlock children may appear as children of a set of grandparents. A divorced person may be listed as a widow, but then the ex shows up with a different spouse in the next census. The wife may be older than the husband, but is listed as younger on the census page.

Genealogist Tom Myles.

Jim McNiff, in common with Tom Myles, isn’t concerned about getting paid. The genealogist who lives in the Boston area with his wife, a fellow Bronx native, is thus free to search for celebrity roots and he has garnered quite a few headlines in the process. McNiff's search into Senator Kamala Harris’s Jamaican roots, particularly the Finegans and Finnegans, was featured in last week’s Echo and 11 months ago we covered how he came to find Robert De Niro’s great-grandmother in Tipperary parish records.

As we all know the census records of the past can be one of the best factual clues when researching our ancestry. However, it can also be one of the most confusing and misleading breadcrumbs in our journey to the past. For example, a common problem is matching the surname. For example, Smyth becomes Smith and Finegan becomes Finnegan. This could be the person you are trying to find but the name changes which causes you to ignore the clue. This can you lead into the dangled forest of data that results in you taking the easy way out and picking the wrong ancestor. Over the years I have investigated many family trees produced on ancestry.com that have selected the wrong person as a great ancestor such was the case when I produced the ancestry of football player Tom Brady.

Here are few bits of advice when investigating a census record:

Before taking a shortcut, look about. What I mean is assume this could be your person however continue to examine future census records to find data that is consistent. If the children on the first record match (let’s say 1900) and the children on the second record (1910) match for age and sex, you will increase the probability of success.

Look about, again. Check families living next to the person you are investigating. You may find a great uncle living a street away. Many of our families had their children living in the vicinity of the parents. For example, Aunt Margaret may have a new surname that you may not recognize. But if you look at the record above the parents you may find that she has married and is living in the apartment next door.

Look about, once more. One field on the census records may state the number of children born to the parents and alongside of it the number that are still alive at time of this census record. This will prevent you from possibly following ancestors that are already deceased. Diseases contributed to the death of many young children who could be on a 1900 census and not appear on a 1910 census.

Jim McNiff, center, did family research for Margery Eagan and Jim Braude of WGBH.

My primary bit of advice is that the census records alone may not tell the full extent of your family history. They should be matched to naturalization records (my best resource), birth and death certificates and any other factual documents. One dangerous approach is to copy from other people who seem to have the same ancestors as yours. First check that they have the records (census and other) and review their findings before you decide to make them yours. Do not let your frustration drive you to a history that is not yours. And remember ancestry shows on television do not provide the reality of the time and effort required to get the product they are displaying. It is your family; it is worth the time and effort to get it right.