[This article is one in a short series History by the Book. For two others in the series click here and here.]

“Three key aspects of the Union struggle at Gettysburg [July 1-3, 1863] comprises the core of the Irish-American memory of that struggle,” writes Susannah Ural Bruce in “The Harp and the Eagle, Irish-American Volunteers and the Union Army, 1861-1865.”

The first centered on Col. Paddy O’Rorke’s leadership of the 140th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment’s efforts at Little Round Top. The third was the 69th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry Regiment’s involvement in the Union defense of Cemetery Ridge during Pickett’s Charge.

The second, chronologically, was the story of Col. Patrick Kelly and the 88th New York. Kelly lead his 500 men — as one of Irish Brigade’s officers noted of its reduced numbers, “now a brigade in name only” — into the waist-high wheat field owned by George Rose. Just before that, at 6 p.m., one of the Irish Brigade chaplains, Fr. William Corby, climbed onto a boulder “so those who could not hear him above the crack of musketry and thundering cannon could see and understand the meaning of his actions.”

He urged them to fight bravely. Any soldier who fell in that field would receive a Christian burial; those who ran would be denied it. “Then he raised his hand as the men knelt and removed their caps, under flags representing Ireland and the United States, and offered a general absolution for the forgiveness of their sins. ‘Dominus nos Jesus Christ's vos absolvat,’ Corby began.”

Even General Hancock, watching from his horse, removed his hat and bowed his head. It was an absolution, Corby said later, for all who were “susceptible to it and who were about to appear before their Judge.”

Then the priest watched as the men “plunged into the dense smoke of battle” knowing “that perhaps in less than half an hour their eyes would open to see into the ocean of eternity.”

Randall M. Miller, author of “Union Soldiers and the Northern Home Front,” wrote ”With remarkable sensitivity and acuity [Ural, she later dropped the last part of the name professionally] goes digging among the personal and public accounts of the Irish soldiers in the Union army and presents these soldiers, and their families and communities, on their own terms so that they emerge as real people conflicted and changed by the demands of war and the obligations of 'community.' The result is a book of immediate interest.”

The Journal of Southern History called Dr. Ural’s work, originally published in 2006, as "The best book ever published on ethnic units in the American Civil War.”

One of the most discussed chapters in Irish-American history, happened at a moment when people of that heritage were Irish-born, with accents that identified them as such, in jobs that put them at the lowest rungs of the socio-economic ladder for free men. They had close family ties in Ireland and were considered aliens, with an un-American religion.

One way to reflect upon the episode is to look at the percentages of Irish-born in major cities: here’s a selection in 1860 on the eve of the Civil War. New York 26 percent, Brooklyn (then a separate city), 22, Philadelphia, 18, Boston, 26, St. Louis, 19, Chicago, 18, Albany, 37, San Francisco, 17, Lowell, 26, Detroit. 14, Pittsburgh, 19, Jersey City, 26,

Ural looks at the then recent American history to put some of the time in its context. She quotes Robert Smith, a Protestant from County Antrim, who found a position as a custom house official in Philadelphia, one of three Irishmen out of 200 employed, in part on merit, but also he conceded because of his ties to President John Tyler.

“Our city has been nothing but the scene of bloodshed,” he wrote in letter home in 1844. “The problem being native American citizens forming themselves into a body to deprive all the foreigners of their rights and privileges guaranteed to them by the Constitution. The rage was focused on Irish Roman Catholics and at one of their meetings the Irish rose against them and there was a great number shot on both sides. There were a great many Roman Catholic churches and nunneries burned in this city and as many as 50 killed in one night.”

Back in that era Irish leader Daniel O’Connell’s anti-slavery views became an issue for the Irish to grapple with; they were condemned by no less a figure than Archbishop John Hughes of New York. The Boston Pilot said that abolitionism was “thronged with bigoted and persecuting religionists; with men who in their private capacity, desire the extermination of Catholics by fire and sword.” O’Connell would in time denounce the support of slaveholders and Irish-Americans who associated with them. But for Catholics in America, slavery was a political issue not a moral or theological one.

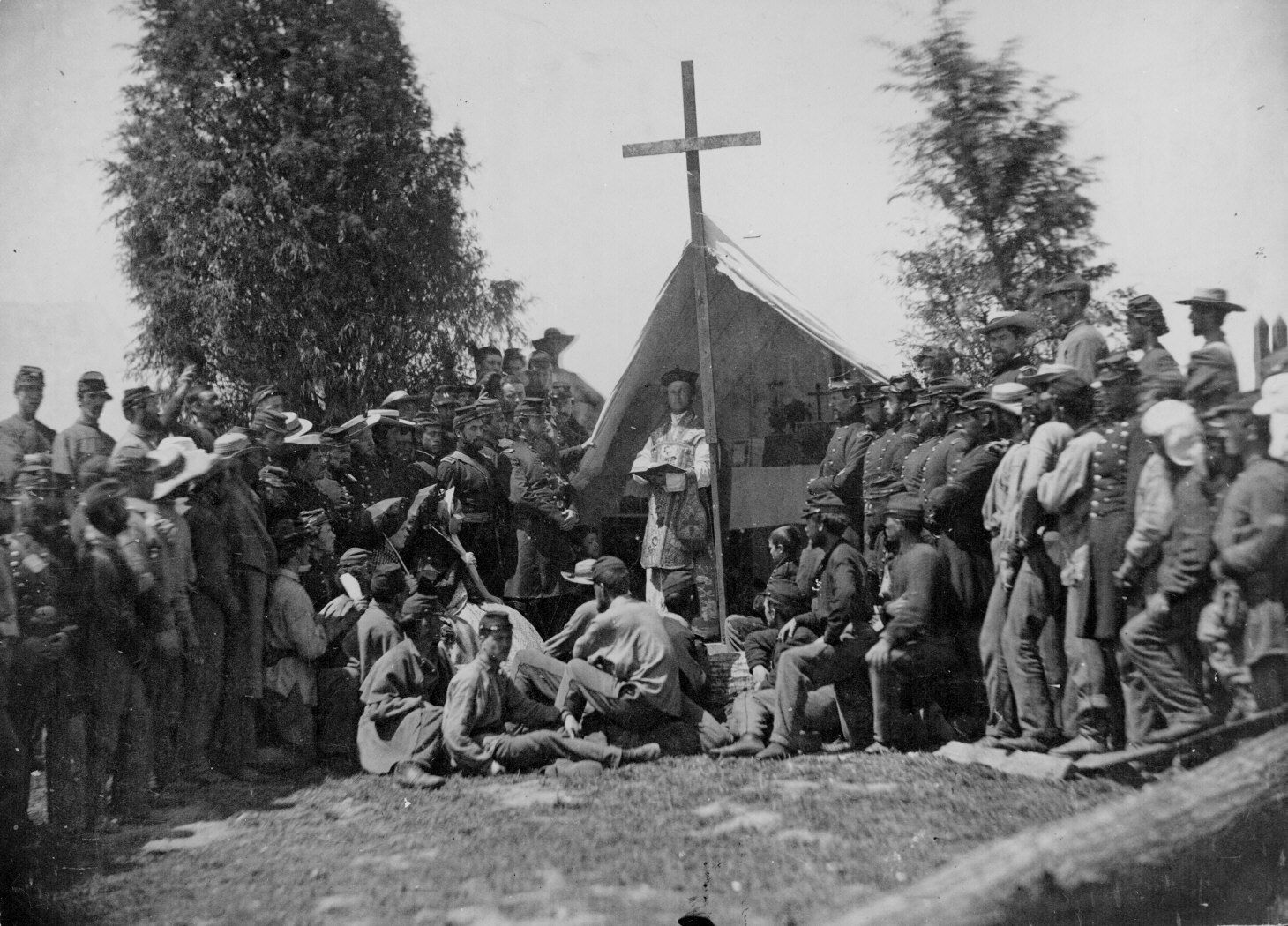

Fr. Thomas H. Mooney, Chaplain of the 69th Infantry Regiment of the New York State Militia and Irish American soldiers at a Catholic Mass at Fort Corcoran, Arlington Heights, Va. on June 1, 1861. Mooney was soon recalled to New York because of his overly war-like language.

Meanwhile, the Irish were gradually finding their way into the military. The U.S. Army offered opportunities for people on the lowest socio-economic categories steady. Ural writes that scholars have generally overlooked the armed forces from the perspective of the lowly immigrant, and how its poor pay and conditions could actually be a step up for him, first of all by providing a steady income, when other work was so often intermittent. Service and the learning of American ways and traditions might also lead to work outside of the military.

The economic benefits continued to draw immigrants during the American Civil War, but particularly towards the end when enlistment bounties offered were attractive. Back in 1850 and 1851, before any such inducements were available 3,516 immigrants joined the army, of which 2113 were Irish. Into that decade, the army was made up of two-third immigrants, and 60 percent of those were Irish. But they faced nativist, anti-Catholic and class prejudice.

A Scottish recruit and veteran of the British army referred to the treatment of immigrant soldiers at the hands of “ignorant and brutal officers” as “barbarous,” [which] “were I to relate it in minute detail, would seem almost incredible.” Future Civil War military leaders George Meade and Ulysses S. Grant recognized the need to work against anti-immigrant and anti-prejudice in the military ranks.

General Grant in 1861.

The Irish were put on the defensive by the San Patricios incident, in which soldiers defected during the war with Mexico. Though the Catholics involved were from diverse backgrounds, their leader John Riley was indeed from Galway; however, the Irish-American press claimed he was from London. The Pilot editorialized, “Instead of stirring anti-Irish and anti-Catholic rancor by dwelling upon this imposter, why do not the nativist papers pay attention to another Riley, the brave and gallant colonel, who has distinguished himself so valiantly?” Grant himself said that Bennet Riley, born into a poor Irish-Catholic family in Maryland in the late 18th century, “was the finest specimen of physical manhood I had ever looked upon…6’ 2” in his stocking feet, straight as the undrawn bowstring, broad-shouldered with every limb in perfect proportion, with an eye like an eagle and a step as light as the forest tiger.”

This was the pattern that Ural outlines that would continue into the Civil War — praise and prejudice. It helps explain the Irish preference for their own units. As the most famous of the Irish military leaders, Thomas Francis Meagher, argued, it was the only way their valor would be recognized. And so it proved.

The Irish, both North and South (as we saw last time, when discussing David T. Gleeson’s book “The Green and the Gray”) backed Stephen Douglas in 1860. The Pilot in Boston described Abraham Lincoln as a “very weak man intellectually.”

The Irish-American newspaper in New York said, “We deprecate the idea Irish-Americans—who have themselves suffered for opinions’ sake not only at home but here even—volunteering to coerce those with whom they have no direct connection.”

Says Ural, “Even the future leader of the Irish Brigade Thomas Francis Meagher defended the rights of southern secessionists, even going so far as to challenge the term ‘rebel’ as disrespectful to Confederates. ‘You cannot call eight millions of freemen “rebels,” Meagher argued, preferring the term ‘revolutionist.’”

Later she writes, “Once Confederate forces fired on the Federal arsenal at Fort Sumter, South Carolina, however, Irish-American opinion in the North swung solidly behind the union. Meagher came to believe that his loyalty to the United States was as significant as his work for Irish freedom. In this respect, he captured the feeling of many Irish-Americans who did not support abolitionists, nor the Republicans, and yet could not remain inactive during a conflict that threatened to destroy the nation.”

Quartermaster Joseph B. Tully, quartermaster of 69th New York State Militia, explained their position: “The 69th regiment is composed of men who have always stood by the South in a constitutional way. They have never had any affiliation with abolitionism, but their regard for the South is far from equaling their love for the Union. The latter ‘must and shall be preserved,’ if the blood of ourselves and all who feel as we do can effect that preservation.”

And, Ural says, Irish-Americans answered President Lincoln’s call “by volunteering in astonishing numbers.”

Thomas Francis Meagher.

The New York Times got swept up in the excitement of the 69th Regiment departing the city for Washington in April 1861: “When Sergeant-Major Murphy, bearing the magnificent national standard of the Regiment, and the Color Sergeant, with a splendid silk Star-Spangled Banner, also the property of the Regiment, appeared in Great Jones Street and unfurled the united standards of Old Ireland and Young America, the enthusiasm of the soldiers and the surrounding masses was wholly indescribable.”

One cry heard on that day was “Remember your Country and Keep Up its Credit!” It wasn’t clear which country was being referred to. But any native-born Protestant uneasiness with Irish dual loyalty or with non-American imagery was put on hold.

Writes Ural, “For a brief time, the causes of American Protestantism and Irish-American Catholicism cooperated with astonishing efficiency. It would a fragile relationship, though, that had long-term ramifications for the Irish postwar America.”

The 69th set about constructing their headquarters at Arlington Heights, Va., and when it was finished the War Department instructed that it be named in honor of Michael Corcoran, its colonel. When the regiment’s chaplain, Fr. Thomas Mooney, controversially “baptized" a cannon at Fort Corcoran and urged its soldiers to “flail” the enemy, he was ordered by Archbishop Hughes to return to his St. Brigid’s parish in Manhattan. The author said, “While he would always be quick to chastise the Lincoln administration or the media for failure to recognize Irish sacrifices in this war, Hughes was equally quick to rein in any member whose actions might reflect poorly on Irish Catholics. He was well aware of the spotlight on his flock.”

The men of the 69th made an almost immediate impact at the first Battle of Bull Run. “Many of the men were bare-chested,” writes Ural, “having stripped down in the heat of summer and the battle, and Colonel Corcoran led his men into the fray, a journalist from Harper’s Weekly captured the scene with a romanic sketch of the 69th for this paper, describing how the Irishmen had ‘stripped themselves, and dashed into the enemy with the utmost fury. The difficulty was to keep them quiet.’ The image contrasted sharply with the one of disloyal Irishmen Harper’s Weekly had painted just nine months earlier following the Prince of Wales incident [in which Corcoran, a leading Fenian, had refused to parade the regiment].”

Colonel Michael Corcoran.

Now, she continues, “native-born and Irish-Americans alike celebrated the stereotype of the rugged Irish ‘race’ in their favorite element, a good fight. A certain level of prejudice remained in references to Irishmen as ‘natural’ fighters, an image of violence that had plagued them in the 1840s and 1850s, but now the Irish were using such stereotypes to their advantage.”

The 69th arrived back at Fort Corcoran, at 3 a..m. on July 22, 1861. Thirty-eight were killed and 59 wounded, while 95, including Corcoran himself, were missing. Some in the last category had seen enough of the war and the rest had been taken prisoner by the enemy. Those figures were low compared to the staggering losses Irish units would incur in key engagements in the next couple of years.

The New York Herald reported on a visit to the headquarters by Lincoln and Secretary of State William Seward: “The term of the 69th has expired, but upon Mr. Lincoln—who complimented them on their valor and valuable services—asking them to reenlist, they declared, with loud cheers, their determination to do so to a man, and see the fight out.”

Corcoran, it turned out, was captured. And when some Confederates were accused of piracy and faced the possibility of death sentences, Jefferson Davis threatened he would execute Union prisoners. Corcoran was selected and made headlines by saying he was ready to make the sacrifice. Overall, he emerges as a much less complicated hero in the story than his fellow Fenian Meagher.

Some of Corcoran’s men after being captured by Confederate forces on July 21, 1861.

Lincoln, of course, had a key role to play, even after death, as the Irish found to their cost. His martyrdom only reinforced the prestige and hegemony of the party they voted against. The president had been fair to the Irish, though. For example, when the Draft Riots debacle put the Irish on the defensive again, shortly after the heroism of Gettysburg, he saw it as a question of divisions between working men, who should instead unite. Unfortunately, his words on such occasions were often twisted in the Democratic and Irish press.

For their part, the Irish couldn’t get much of a break. Ural points out that time and again, their sacrifices and the fact they’d contributed 150,000 men to the Union cause were ignored or belittled. And so they learnt to commemorate the Civil War in their own ways.

Out of the great military conflict, too, they came to realize that there was strength in numbers.

Ural writes, “Irish-Americans’ determined self-reliance and their focus on Irish-American interests helped them acquire power and influence within the American political system.”