On a recent WNYC show, a therapist offered some of the usual advice for couples currently spending rather more time together that they’re used to. More interesting were her words of wisdom for people who are far apart from their significant other during these perilous and unsettling times; she suggested writing letters the way people used to, and in the same vein recommended imagining one was living at a different time in history.

Good advice certainly, and one might add, too, that if the “past is another country,” as is often said, then reading history might provide a short-term fix when we can’t go anywhere, much less overseas.

And perhaps this could be a good moment to delve into the Irish-American experience. With a view to helping that end, the Irish Echo is recommending three fascinating and accessible works by scholars with a speciality in the area. The first of them focuses on the urban experience, specifically in New York, and two center around the impact on the diaspora in North America of its involvement in the Civil War. [For those latter two see here and here.]

We have to acknowledge a certain bias in the first selection, “Machine Made: Tammany Hall and the Creation of Modern American Politics,” as it’s written by sometime Echo columnist Terry Golway, who has combined careers as a history professor and a prolific journalist.

Golway tells the story of an institution that still tends to be remembered for the corruption of two of its leading bosses in of late 19th century — William Tweed and Richard Croker.

Terry Golway is the author of “Machine Made: Tammany Hall and the Creation of Modern American Politics.”

Tammany was also at the very heart of the great melodrama of urban affairs from the Civil War onwards, which pitted those who openly practiced transactional politics based on patronage — jobs for one’s loyal voters and lucrative contracts for backers — against those mobilizing under the banner of good government and reform. However, what may be business as usual at the highest levels of our politics today— with only the most explicit quid pro quo missing — doesn’t take place at the neighborhood level any more, and folks tend to cast a disapproving backward glance at the corrupt practices of long ago.

Golway's revisionist account reveals a far more complicated picture: one in which oppressed immigrant working-class Catholics did battle with moralistic middle-class native-born Protestants, who lived far from the reality of urban poverty. The former, mostly Irish from the time of the Famine until after the turn of the century, wielded an existing structure (the Tammany Society was founded in the 1780s) and well-established forms of political practice to their own ends — the most notable of which was rapid acculturation and assimilation into American life.

“From the moment they landed in Lower Manhattan, the Irish embraced what Daniel Patrick Moynihan called the ‘possibilities of politics,’” Golway writes in his introduction. “Their enthusiasm for the handwork of organization as well as the grand spectacle of political performance has been attributed to their command of the English language — although many immigrants arrived in New York speaking only the Irish language — and to their supposed gregariousness — although the man who led Tammany from 1902 to 1924, Charles Francis Murphy, earned the well-deserved nickname ‘Silent Charlie’ for his closed-mouth style of leadership.”

Just as “Honest John” Kelly had to pick up the pieces after the fall of Boss Tweed, so Murphy had to steady the ship following the scandals surrounding the one-time Kelly lieutenant Croker. Murphy was born in 1858 to Irish immigrant parents in the Gas House District on Manhattan’s East Side. He was in life as shrewd a businessman as he was a political operator, and acquired his first saloon in his early 20s and soon had four of them.

In politics during his rise, he impressed with his ability to get out the vote for the entire ticket and “that talent,” writes “Machine Made” author Golway, “mattered more than anything else in a political organization whose power rested not on claims to moral or cultural authority but on the perception of mass public approval and the reality of loyal voter turnout.”

The professional politician should know how to listen, not to talk, in Murphy’s view. A journalist wrote in the New York Times, “His long suit is asking questions. He is an insatiable interrogator.”

Political picnic

Commentators like Mark Twain thought Tammany was finished after Croker, but Murphy adapted to new times. A devout Catholic, he ordered an end to any Tammany association with gambling, prostitution and outright bribery, but his view of clean government “did not preclude the awarding of contracts to politically connected companies,” Golway says. He was a beneficiary himself, as were his brothers. And of course the once highly-rated baseball player and oarsman was all for sports on Sundays, and as a saloon keeper, he was opposed to those who wanted to restrict drinking hours, or indeed ban drinking altogether.

Murphy was perhaps the last of the great Tammany household names, but there were politicians — like John F. Ahearn, variously a state senator and state assemblyman for the Lower East Side — that were powerful figures within a Manhattan organizational structure based around the clubhouse. Golway says the the clubhouse system, which allowed Tammany to dominate Democratic Party politics in New York County, was “remarkably similar to the system of Liberal Clubs that Thomas Wyse had founded in Ireland after the Catholic Emancipation campaign in Ireland in the late 1820s.”

Ahearn’s own clubhouse, the John F. Ahearn Association on Grand Street and East Broadway, was the center where, said Tammany operative Louis Eisenstein, thousands of new and soon-to-be citizens found an “impersonal government translated and interpreted here by the personal touch.

The Lower East Side's John F. Ahearn.

“To where besides the Tammany clubhouse could a white-bearded, 80-year-old patriarch go for assistance,” Eisenstein recalled. “Unable to speak or write a word of English, he would seek out our Irish leader.”

Golway says that clubs and Tammany-associated political associations “fostered a sense of community and common purpose in neighborhoods that were home to newcomers from Southern and Eastern Europe.”

The Ahearn Association sponsored an annual cruise to picnic grounds on the banks of the Hudson River. The New York Times described the 1893 event, which took 20,000 on six barges and two steamships, as the “biggest pleasure party that ever left this city by way of water.”

The annual cruise and picnic, comments Golway, enhanced Ahearn’s popularity and “emphasized Tammany’s commitment to spectacle and service.”

When he died in 1920, the Times editorialized, “As a district leader, Ahearn exemplified to a high degree the Tammany type in his intense and constant playing of the political game and his devotion to the intimate personal needs of the men and women in his district.”

Factory calamity

Tammany, which had had to contend from the 1880s with a challenge from the progressive economist and author Henry George and Fr. Edward McGlynn among his prominent radical backers, itself moved left in the early 20th century, partly under the influence of worker-friendly Catholic clerics in the American hierarchy.

Then calamity — the deaths of 123 women and girls and 23 men in the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in March 1911 — became a new impetus for reform. Eventually, social legislation backed by leading Catholic Tammany pols in Albany like Al Smith (a future governor and presidential candidate) and Robert Wagner (a future influential U.S. senator) together with progressive Protestant social reformer Frances Perkins would become the basis of the New Deal two decades later.

“At the height of its influence, Tammany Hall supported the writing of a new social contract in New York, one that served as a model for a more aggressive role for government in 20th century American society,” Golway writes.

Murphy’s part in the the 1912 Democratic Convention in Baltimore marked the arrival of the urban Irish on the national stage, argues the author. Having a majority of those traveling from New York in his pocket, the boss had a complete lock on the single largest delegation, according to the state rules at the time. This meant that Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who would always have a complicated relationship with Tammany, had to vote in Baltimore whichever way Murphy directed him to.

Murphy’s main aim was to prevent three-time losing presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan becoming the standard-bearer for a fourth time. Although a rural fundamentalist Protestant, Bryan was the Bernie Sanders of his day when it came to opposing big business. Here he differed with the Tammany approach, which emphasized compromise over confrontation. Asked by the press about Bryan’s comment that Tammany was close to “predatory Wall Street interests,” Murphy said that the rural populist “had a right to say what he chooses,” and adding about himself, “I have a right to be silent.”

Ultimately, Bryan backed Woodrow Wilson as the least objectionable of the serious candidates available, and Murphy, too, would cast New York’s 90 votes for the governor of New Jersey and former president of Princeton University.

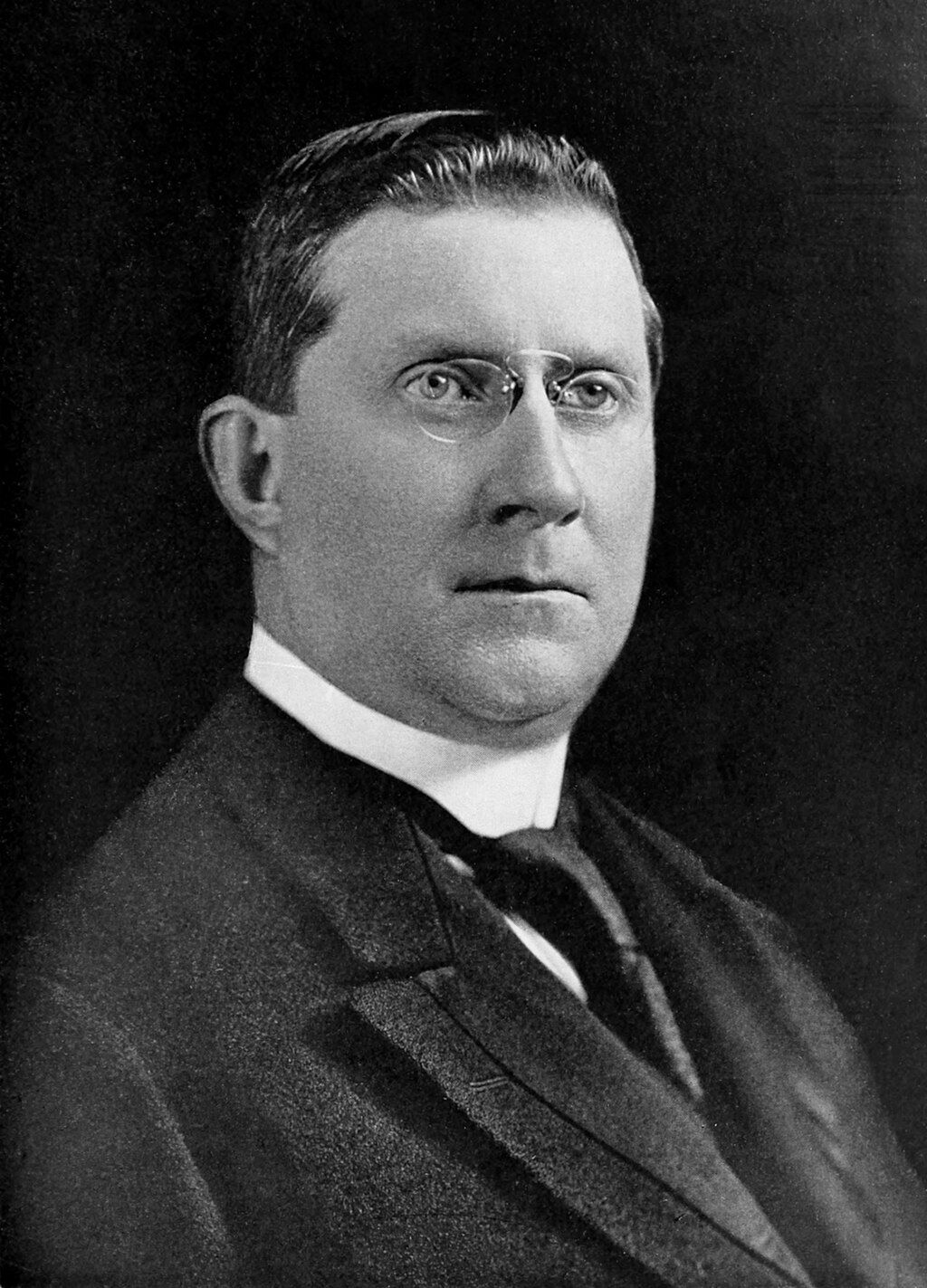

On Inaugural Day 1913, the following March, President Wilson pointed out to his wife the, in the author’s words, “bespectacled, paunchy and dignified” man leading the Tammany delegation in the afternoon-long parade: “That’s Charlie Murphy.”

President Woodrow Wilson.

Hard-headed pols

Perkins, who’d forged a working alliance with Murphy’s men, would 11 years after his death be appointed secretary of labor in the incoming FDR administration and in time the New Deal’s most enduring political figure after the president himself, serving in the post as she did for his entire 12 years in the White House.

Already by 1936, Senator Wagner could say in a keynote address that “Tammany Hall may justly claim the title of the cradle of modern liberalism in America.” But that speech’s verbs were tellingly in the past tense, Golway notes. With the flow of immigrants halted and the New Deal programs catering to the masses, the need for machine politics was largely gone.

Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins.

During the early war years, Tammany left Tammany Hall at Union Square, moved uptown to a Madison Avenue office and renamed itself the Democratic County Committee of New York County.

The author writes, “Inside [the new office] there was just one glimpse of glory decorating the walls: a fine old oil painting of Charles Francis Murphy.”

His proteges, though, were still hard work at this time. One of them, FDR aide and Bronx leader Edward Flynn, realized whoever was on the bottom half of the ticket in 1944 could be president before too long. The incumbent Vice President Henry Wallace had in his view moved too far to the left, and so Flynn with other hard-headed Irish political professionals plotted to remove him. His co-conspirators included Mayor Ed Kelly of Chicago and Democratic National Committee chair Robert Heneghan. They would settle on Senator Harry S. Truman from Heneghan’s own Missouri as a replacement. As mentioned in these pages a couple of times very recently, the senator’s political rise came courtesy of the Irish machine in Kansas City, led by Thomas Pendergast, who on the eve of World War II had been convicted of income-tax evasion.

“Truman was neither Irish nor Catholic,” Golway writes, “but, like Franklin Roosevelt, he came of age in a political culture that was both.”

The series will return to the Irish-American urban experience on April 29, but in next week’s digital edition (April 22) our book looks at an important, if generally unexplored, aspect of Irish immigrant involvement in the Civil War.