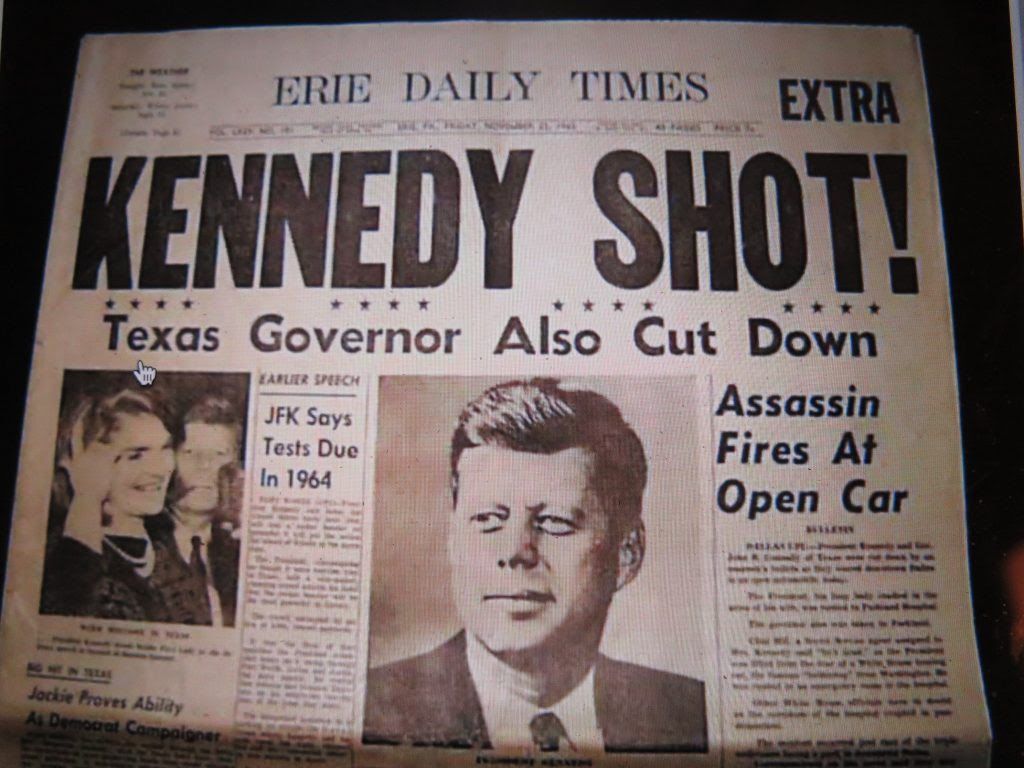

This Erie Daily Times from Nov. 22, 1963, has a report with a quote suggesting that President John F. Kennedy was dead on arrival at Parkland Hospital. The quote tends to be forgotten, even though the source was a high-profile eyewitness and government employee and it was relayed via a UPI journalist who won the Pulitzer Prize for his work on that day. TIMOTHY HUGHES RARE & EARLY NEWSPAPERS

Screen Time / By Peter McDermott

“From Dallas, Texas: flash, apparently official, President Kennedy died at 1 p.m. Central Standard Time,” Walter Cronkite announced. He looked upwards to his right for a moment and then again, before adding, “2 o’clock Eastern Standard Time, some 38 minutes ago.”

I wonder will people in another 57 years get that the famed CBS News anchorman was checking a clock on the wall, and not a screen or something outside a window that had distracted him. Will there be clocks in 2077, other than Big Ben and the one at Grand Central Terminal?

The moment is rightly iconic and will remain so. We can see Cronkite regaining composure after a momentary break in his voice, putting on his reading glasses and continuing with news of Vice-President Lyndon Johnson. It all took on great symbolic value as the years passed.

Cronkite would become the “most trusted man” in America, precisely because of the sort of professionalism he displayed on Nov. 22, 1963, The CBS anchor had been waiting for the official announcement, which came from the assistant White House press secretary Malcolm Kilduff at Parkland Hospital. It tended to confirm what most Americans had already come to believe in the minutes leading up to it — their 46-year-old president had been assassinated.

One report on the day itself became a confirmation for most; it was widely disseminated six minutes before Cronkite’s announcement. An episode of “Mad Men,” broadcast first in November 2009, and set on the weekend of Nov. 22-24, 1963, made this point with a clever story-telling device. Herman “Duck” Phillips, a divorced advertising executive, is waiting in a midtown Manhattan hotel room for his young lover, Peggy Olson. Back at the agency that is at the center of show’s storyline, Cronkite’s voice comes in over the lunchtime soap opera “As The World Turns” in someone’s office, unnoticed as the volume is down low. Duck hears the report, though, and takes the plug out of the wall socket. He is presently joined in the hotel room by Peggy, a rising star in the industry.

Actually, in New York, ABC Radio news was first with the story when it interrupted Doris Day singing “Hooray for Hollywood” at 1.36 — or 12.36 in Dallas just as the presidential limousine reached Parkland. The ABC Radio newsreader Don Gardiner struggled even more dramatically with his emotions at times than the CBS anchor as he delivered the dire news, in particular a report given at about 12:45, from the wire agency United Press International, which contained the dramatic quote from someone who was well-placed to know — “He’s dead.” More on that below.

In the “Mad Men” episode directed by the Swiss movie-maker Barbet Schroeder, who was 22 in 1963, the suburban housewife Betty Draper sits anxiously on her living-room couch watching NBC News. She’s holding a lit cigarette. The hammer blow comes when anchorman Bill Ryan says that two priests who were with President Kennedy “say he is dead of bullet wounds.”

The child-minder/maid Carla, an African American, arrives at that moment with the two children from school and asks, “Is he okay?” Betty says, “They just said he died.”

Carla looks heavenward and says “Oh, Lord!” She sits down beside Betty, takes a cigarette from her own purse and lights it. The women, both distraught, quietly weep.

Duck switches the TV back on in the hotel room at precisely the moment of Cronkite’s famous announcement. A shocked Peggy hears the news as it’s made official, which is later than just about everyone else.

Preparing the soul

There are six main characters in the 1960s-set show that was initially broadcast from 2007 through 2015. All are white; only Peggy, a Catholic from Brooklyn, could be described as “ethnic” — her late father was Norwegian American, while her mother is an Irish American.

When she later gets her own apartment in Manhattan, Peggy (Elizabeth Moss) has a portrait of JFK on one wall. In the previous season, set in 1962, she grapples with matters of faith; a visiting priest to her mother’s parish, Fr. John Gill (sympathetically played by Colin Hanks, son of Tom Hanks), is her confidant.

NBC’s Frank McGee and Bill Ryan on the afternoon of Nov. 22, 1963.

The real-life Rev. Oscar L. Huber, 70, was dealing with mighty theological questions on Nov. 22, 1963, and in interviews in subsequent days and weeks, such as when does the soul leave the body? He explained to a non-Catholic audience that a good Catholic was usually sorry after committing a mortal sin, and being sorry was sufficient. Someone like President Kennedy was fully aware that he faced danger in any room or space he entered. The priest was confident that he would have prepared his soul for the eventuality of sudden death.

Huber grew up on a farm near Perryville, outside St. Louis. He entered the local Vincentian seminary only after his younger siblings had been educated. He was 28 and had to complete his own final two years of high school. The good-humored priest was popular and well-liked in the places he served, such as Kansas City in his native Missouri and San Antonio. Fr. Huber was by November 1963 the pastor of Holy Trinity Church, Dallas. He joined the 250,000 who cheered the president and the first lady along the motorcade route just after 12 on Friday, Nov. 22. He waved at Kennedy and was sure that the first Catholic president saw his Roman collar and waved back. Delighted, the priest returned to Holy Trinity Church. When he got there, however, one of his assistants, Rev. James N. Thompson, who was watching television, informed him of the shooting. They decided to drive to Parkland, which was in the Holy Trinity parish.

Fr. Oscar L. Huber, the pastor of Holy Trinity parish in Dallas in 1963.

When Huber got to the emergency room before 1 p.m., the president’s face was covered with a white sheet. The priest administered the last rites of the Catholic Church. Outside in the corridor, he offered his condolences and those of his parishioners to Mrs. Kennedy. Asked a little later if the president was dead, Fr. Huber said, according to the Associated Press, “He’s dead alright.”

Only 4 percent of Americans first learned of JFK’s death by reading about it in a newspaper. The rest heard about it from electronic media (47 percent) or by word of mouth (49 percent). But print was something very tangible and a real reminder of the most traumatic news event in a generation. I know that my parents stashed away some newspapers from those sad days, while my 19-year-old uncle kept a boxful of them.

Timothy Hughes Rare & Early Newspapers, based in Williamstown, Pa., has a particularly interesting item on sale from the early afternoon of Nov. 22, 1963. The Erie Daily Times’ “Extra” edition contains a report suggesting the president was dead on arrival at Parkland. Some background is necessary here. The great winner journalistically on the day was Merriman Smith of UPI, whose first two reports, coming via the “wire car” a few cars back from the presidential limousine and then a telephone in the hospital, formed the basis of the word getting out nationally and globally. Cronkite combined them for his initial report on CBS. Meanwhile ABC Radio, first on air as mentioned, spaced them and then added Smith’s third bulletin, which contained a quote from Clint Hill, the Secret Service agent famous for pushing Mrs. Kennedy back into the limousine seat just after the shooting. “How badly was he hit, Clint?” the UPI man asked the agent just after they’d reached Parkland. “He’s dead, Smitty,” came the reply. And it was while reading that the Secret Service agent assigned to the first lady had said the president was dead that ABC Radio’s Gardiner struggled to contain the emotion in his voice. It was a full 50 minutes before Cronkite relayed the official announcement.

The Hill quote wasn't backed up by a second source and it seemed half forgotten as other news came in over the next hour or so. The former Secret Service agent himself has not mentioned it in interviews in the years since. He was almost certainly traumatized when he said it, just as Fr. Huber must also have been when he was quizzed by reporters.

The rare papers’ seller Timothy Hughes heads the item with a question: “Kennedy still alive as of this report?” Officially, yes. Hill made the comment at about 12:36, just after the car arrived at Parkland, But of course in reality, no — the president had been killed instantly, which is what Hill was saying. In any case, this rare item featuring the words of a Secret Service agent, later commended for his bravery, via Smith, who won the Pulitzer Prize, might be seen as a steal at $88 by some assassination buffs (like perhaps Manchester United’s former boss Alex Ferguson).

Walter Cronkite in 2004.

An otherwise informative 50th anniversary piece in the New York Observer, then owned by Trump son-in-law Jared Kushner, about how the story broke on Nov. 22, 1963, downplayed the role of Huber and Thompson in bringing news of JFK’s death on that Friday afternoon.

“The priests’ report was more confirmation of what everybody already knew. Mr. Smith’s initial reports made it seem likely that Kennedy was dead,” the Observer said in 2013, “and the TV networks carried unofficial reports that he had died based on sources at the hospital and among Dallas cops.”

Well, actually no. The hours upon hours of TV and radio stuff available on YouTube would suggest that the 2009 “Mad Men” episode got it right. Smith’s bulletins were followed by several reports from all sorts of reliable people — including one U.S. senator, two congressmen and White House aides — that the president was still alive in the hospital. Additionally there was talk of blood transfusions and callouts for specialist doctors. The NBC team of Ryan, Frank McGee and Chet Huntley did not relay any unconfirmed reports or rumors. It was only after the priests’ bombshell via the AP that the local affiliate’s Charles Murphy told them Dallas’ police officers had been informed a few minutes beforehand that the president was dead — news that Murphy said “substantiated” but didn’t yet confirm officially Huber and Thompson’s account.

‘Close to official’

CBS cut a bit earlier to the Trade Mart, where the president had been scheduled to speak at lunchtime and where now the local reporters seemed convinced that the worse had happened; but the national anchor Cronkite was clearly not going to indulge in the rumors and unofficial reports from a city in chaos. He did report at almost 28 minutes past the hour that the network’s Dan Rather in Dallas said the president was dead. However, even after that the anchorman mentioned one report that he was still alive, which was according to Fr. Huber, who had been with him in the ER a few minutes before — though this appears to have been speculation on the pastor’s part about the soul and the body. Cronkite also said there was no word yet on the “extent” of the president’s wounds. And while he talked about the “probable assassin,” CBS was still dealing in the realm conflicting information. That all changed with the AP report about the priests saying the president was dead, broadcast at 32 minutes past the hour. “That seems about as close to official as we can get at this time,” Cronkite said.

Indeed, Fr. Huber shredded all hope. There wasn’t a single reference anywhere after that report to the possibility that JFK might still be alive. It gave permission, as in the case of Murphy and the Dallas cops, for journalists to go official with their own sources. For other outlets, it was the last direct report from Parkland; they did not refer to the official announcement, though they certainly heard it. Instead, they simply declared that President Kennedy was dead.

And “close to official” was enough for local Dallas TV station WFAA-TV, which seconds after the AP report about the priests posted a picture of the president accompanied by the words and numerals “John Fitzgerald Kennedy, 1917-1963.”

Walter Cronkite, of course, was absolutely right to be cautious about the reporting on Nov. 22, 1963. AP, for instance, make several errors: among them its news that a Secret Service agent had been killed and the vice-president wounded. It was more important to be right than to be first, the anchorman believed. And if you were wrong on some detail, you had to correct it.

On Saturday, Jan. 8, 2011, NPR announced that Congresswoman Gabby Giffords had been assassinated in Arizona. It was a huge embarrassment for the radio network and it conducted an internal inquiry into what went wrong with the reporting of the mass shooting on the day.

The longtime CBS News anchorman, however, was worried about something much worse that a network’s embarrassment. From the 1950s on, he had witnessed first hand the weaponizing of journalists and the media, particularly from the right. Cronkite, who died in 2009, viewed with concern the rise of Fox News and seemed to see on the horizon a time when an honestly reported and well-sourced story could be labeled as fake.