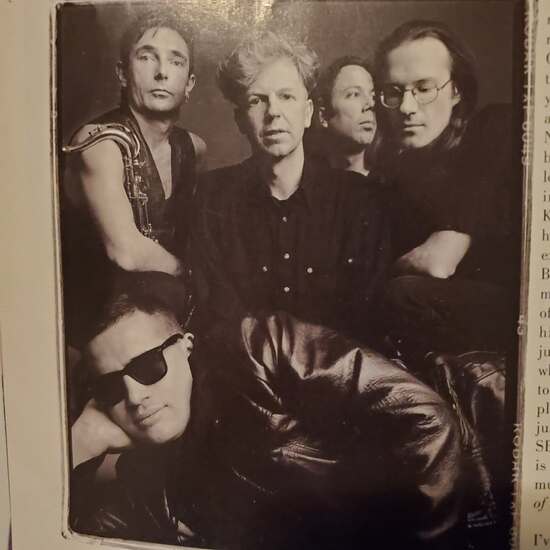

The Whileaways.

Music Notes / By Colleen Taylor

I love Irish Americana—Eirecana as it’s sometimes called—because it sounds like home. The home I’m talking about is not a physical domestic space or a region on a map but rather the feeling of an imaginary pseudo-nation in which I, like so many other Irish Americans, feel most comfortable, most like myself. I like to think of this imagined nation-space as somewhere in the middle of the Atlantic, halfway through the Aer Lingus flight, where the idea of singing “The Fields of Athenry" after Thanksgiving turkey is not so incongruous, or where “March madness” means both basketball games and an endless itinerary of St. Patrick’s Day parades. It’s a place of perfect liminality, the bedrock of Irish-American identity and indeed, of Irish Americana. It’s at this point in the flight, or perhaps when I’m feeling like an outsider in either Dublin or Boston, that I listen to the Whileaways, a band that represents the best of Eirecana today. Their latest album, “From What We’re Made” (2018), gave me that comforting feeling of home while also reminding me this home space of in-between, neither fully American nor “really” Irish, is also a place of subtle, dulcet melancholy. Because of course, when you feel most at home in the liminal, it also means you don’t fully belong on either side of the divide. “From What We’re Made,” at every turn gorgeously gloomy and sweetly nostalgic, makes that sadness of being in between beautiful and palatable.

Although they are Galway natives, the Whileaways—a trio made up of Noriana Kennedy, Noelie McDonnell and Nicola Joyce—think like Irish America. Like me, like so many of us, the band views American history and culture through an unavoidable Irish background, and then looks back at Ireland through an Americanized framework. After all, you don’t get to be a band as good as the Whileaways without a history of traditional Irish music, or a serious study in blues, American folk, and country music. Indeed, all three singer/songwriters have their own folk careers outside of the band. Noriana Kennedy, for instance, sang with Solas as lead vocalist for the past couple years. When separate and solo, Kennedy, McDonnell, and Joyce are great, but together they are sublime. The music they make is uncanny: it sounds so familiar and yet cannot be strictly pinned down as either trad or American folk at any single bridge or chorus. Their music is in constant flux: it is neither/nor, both/and. The Whileaways would be black sheep at a bluegrass festival and a fleadh, and yet also belong among those events’ best performers. The band is still relatively new, having released their self-titled debut album in 2013, and their follow up, “Saltwater Kisses” in 2015, but “From What We’re Made” is the music of masters.

I’ve been a big fan of the Whileaways since I first saw them at Whelan’s in Dublin in 2014, and “Saltwater Kisses” is one of my favorite albums, maybe ever. So when I first listened to “From What We’re Made,” I liked it but found myself preferring their two previous albums. I now realize, however, having listened a second, third, fourth time, that my initial impression, like Elizabeth Bennet’s of Mr. Darcy, was completely, entirely wrong and owing to my own circumstances. At first, “From What We’re Made,” sounded almost too familiar, and perhaps I was not ready to recognize their exact, genius representation of the heartbreaking in-between. What’s more, on my first listen, I was walking around Dublin, and to really understand this album, you must be static, sitting still, and doing nothing else. This is music that transports—it will move you back in time to the 19th century and suspend you in air, midway over the Atlantic. And so, to fully appreciate the journey it effects, you must first be still and then let your mind move with the lyrics and notes.

This album is more of a continuous, cohesive whole than 12 separate songs, so it is difficult to single any one track out. Moreover, Kennedy, McDonnell and Joyce harmonize with such precision (even humming in perfect synchronicity) that is difficult to separate out individual voices and moments on the album. Nevertheless, there were some songs that took my breath away, such as “Never Thought.” Here, Kennedy’s vocals are soft and remarkable, subtle and stand-out. I couldn’t help but think of Judy Garland—Kennedy’s voice has that same ability to be strong and soft, that same classic style, eliciting the sounds of my grandparents’ America in the early twentieth century. “Roll Down the Window” was another favorite, offering a peppy reprieve from the album’s languid nostalgia. “Something From the Heart” was one of McDonnell’s best, featuring some soft trad tunes in the background. “Sweetest Song,” featuring Joyce’s lead vocals, was stunning, blending a familiar folk tradition with some modern rhythms. Finally, “I am a Hill” was extraordinary for its lyrics, offering a simple yet profound metaphor and meshing with a long tradition of Irish poetry in which allegory speaks more clearly than straightforward language. “From What We’re Made” proves the Whileaways masters of arrangement and songwriting.

The title “Irish-American” has come under fire in the past couple years. Writer Colum McCann, a Dublin-born New York resident, for instance, has recently denounced the label, refusing to be associated with politicians who use it as an inroads to (often corrupt) power in Washington. We’re no longer laughing at Joe Biden talking about “malarkey,” for instance. But while anyone familiar with Irish history cannot deny McCann’s point, I don’t think his complete dismissal of the title is fair, especially not after listening to “From What We’re Made.” For one thing, you can’t describe this exquisite music without the term. But more importantly, “From What We’re Made” reminds us that Irish-Americanism is not about politics, or at least, it shouldn’t be. “Irish American” or “American Irish” is the stuff of art, better applied to a feeling, a dual, multiplicitous perspective (not a close-minded one), and, of course, a good tune. The Whileaways give expression to that inexpressible feeling—half nostalgia, half uprootedness—that resonates with anyone who considers herself part of more than one culture. This music is inclusive—it embraces other cultures, other eras, and other voices in the true melting pot way. The profound feelings and histories behind “From What We’re Made” defend our culture, perhaps return it, via reverse diaspora, to undistorted (if fictional) idealism. Bands like the Whileaways can remind us that Irish America doesn’t belong to the politicians—but rather, as Arthur O’Shaughnessy, another hyphenated Irishman once wrote, it belongs to the music makers, to the dreamers of dreams.