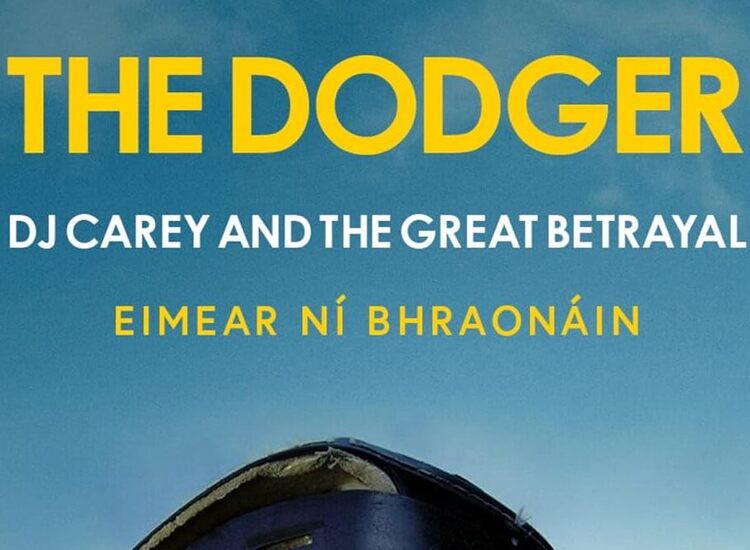

Jamie Dornan in “Siege of Jadotville.”

By Ray O’Hanlon

It was filed away, brushed under the carpet and largely forgotten.

But Jadotville refused to go away.

There were stories, books, and now a movie by way of Netflix.

Jadotville, a dot on the map of a vast country, has stepped into the full glare of history.

As well it should.

“Jadotville is one of the greatest untold sieges in history.”

So says Don Lavery, journalist and expert on the history of Ireland’s military, the IDF, or Irish Defence Forces.

“One hundred and fifty Irish soldiers in 1961 Congo were attacked by anywhere from 3,000 to 5,000 mercenaries backed up with artillery and jets,” said Lavery.

“The Irish killed three to four hundred of them without loss.

“They had to surrender after five days as they were out of ammunition and water.

“Despite their stand, they were effectively blacklisted by the army and government for fifty years.”

Not anymore.

“The Siege of Jadotville,” directed by Richie Smyth and starring Jamie Dornan, was released in Irish cinemas last month.

And the story of the battle fought against overwhelming odds by an independent Ireland’s fighting men is released to the wider world this Friday, October 7, on Netflix.

The movie is based on the book, “Siege at Jadotville - the Irish Army's Forgotten Battle,” by Declan Power, himself a former soldier.

This, however is not the only book about the battle that was officially forgotten, but never by those who saw it for what it was – a heroic stand against all odds.

The other account, “Heroes of Jadotville, The Soldiers’ Story,” is by author and journalist Rose Doyle.

Doyle’s uncle, Commandant Pat Quinlan, led the Irish troops at the Jadotville siege which took place in September, 1961 during the United Nations intervention in the Congo conflict, a mission that followed the attempted secession of the province headed by Katangese Prime Minister, Moise Tshombe.

“Jadotville was the Irish Army's ‘Blackhawk Down,’” said Lavery, whose father, Jim, served in the Congo with the Irish forces.

Continued Lavery: “A handful of surrounded soldiers had to fight tenaciously against a huge enemy force just to survive.

“But unlike the dusty streets of Mogadishu, where U.S. troops eventually fought their way clear, in Jadotville, thanks to UN incompetence, bad tactics and appalling military planning, no help was forthcoming.”

The Irish troops were in the former Belgian Congo after it became an independent Republic in June, 1960.

The newly fledged Congolese government asked for UN military assistance to maintain its territorial integrity.

The Irish government, with Ireland only half a dozen years as a member of the United Nations, agreed to a UN request to send troops.

In September 1961, A Company of the 35th Infantry Battalion was sent to Jadotville, a small Katangese mining town, to protect the European inhabitants from secessionist rebels.

The request to defend Jadotville apparently originated a world away at UN headquarters in New York.

It would turn into a near suicidal mission as the Katangese attacked while being led by Belgian and French mercenary officers who had served in World War II, Indochina and Algeria.

As depicted in the movie, the attack began as the Irish soldiers were attending Mass.

The Irish, who were subjected to intense fire from small arms, artillery and air attack, fought back from their less than formidable defensive positions.

Waves of up to 600 enemy soldiers attacking at a time were mown down by the Irish using everything from elderly Vickers machine guns to modern FN rifles.

Inflicting at least 300 dead, and twice as many wounded on the attacking Katangan force, the Irish had no heavy weapons, no artillery support, apart from a few small 60mm mortars, and no air cover, despite repeated UN promises.

“When the Irish positions in Jadotville came under siege young Irish soldiers fought off the attacks thanks to the leadership of their tough commander, Commandant Pat Quinlan and his NCOs,” said Lavery.

“Repeated rescue attempts by Irish and Indian troops to break through to the besieged outpost failed, the promised UN fighter jets never appeared in the skies, and after days of intense fighting the Irish surrendered.”

The relief column couldn't fight its way through because of a lack of air cover, armor, bridging equipment and other necessary assault and support equipment.

“As usual, UN bureaucracy meant the Irish went equipped for a ‘police action,’ so leaving heavy weapons behind,” continued Lavery.

“In Jadotville, they relied on Vickers machineguns of World War One vintage, Bren lmgs from World War Two, Ford armored cars made in Carlow in 1942, and modern FN rifles and Carl Gustav 84mm recoilless rifles.

“They had no anti-aircraft weapons, poor transport and communications. They were put in an impossible position and they fought like heroes.”

When the Irish eventually surrendered, things could have gone either way.

Massacres were commonplace in Congo at the time and a United Nations badge wasn’t a guaranteed protection.

The Irish, however, had a little Irish luck and were held prisoner for a month before being released.

They should have been welcomed home as heroes.

But that was not to be.

“The soldiers were treated disgracefully by the Irish government and the army because they had surrendered and were shunned and ignored,” said Lavery.

“Instead of a barrel of medals and Quinlan's masterful defense against hugely superior odds being taught in the Cadet College in the Curragh, they were ignored.

“And of course nobody in command, or in government, shouldered the responsibility. The ordinary soldiers who did their duty did.”

It would not be until 44 years later, in 2004, that then Irish Defence Minister, Willie O'Dea, unveiled a plaque in Custume Barracks in Athlone to commemorate the Irish of Jadotville.

They were "ordinary soldiers doing extraordinary things," O’Dea said at the time.

Those extraordinary things will now become evident to a worldwide audience by means of Netflix.

Service in the Congo would be the Irish Army’s coming of age.

Unlike the official silence that followed the Siege of Jadotville, other events would be seared into the collective Irish consciousness - actions and battles that could not be ignored.

First and foremost among them was the Niemba Ambush.

This took place on November 8, 1960, when an Irish army platoon was ambushed and nine of its eleven members were killed by an overwhelming force of Baluba tribesmen armed with poison arrows.

Niemba was the first time since the War of Independence that the Irish army had engaged a non-Irish foe.

Don Lavery’s father, Captain Jim Lavery, was in the Congo in 1960, and again in 1962 when he fought as a Ford armored car section commander in the Battle of Kipushi, winning the Distinguished Service Medal for bravery and leadership.

His armored cars fired 60,000 rounds from their Vickers machine guns that day.

Captain Lavery was also one of four officers sent on a secret mission into Baluba territory to recover the body of Trooper Anthony Browne, who had been killed at Niemba.

He later led a patrol of the 33rd Battalion to rescue priests from their mission which was about to be overrun by Balubas.

Lavery retired in 1974 with the rank of commandant, the Irish army’s equivalent of major.