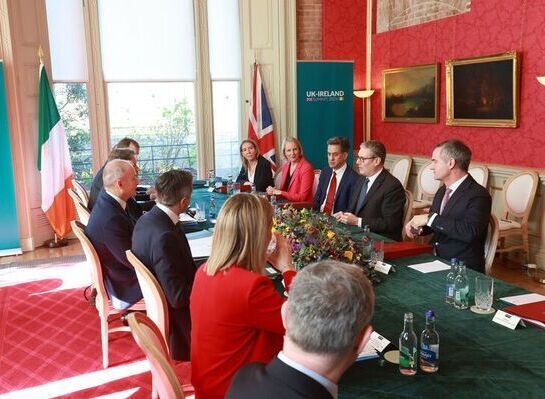

George jpg

George Pataki

By Ray O’Hanlon

rohanlon@irishecho.com

Either the world and its mother is pursuing the Republican Party nomination for next year’s presidential election, or “the mother” part of that total is the only one taking a pass.

But it’s a mother who gives former New York governor George Pataki an entry card to Irish America as he works to gather support for his own, lately unveiled, presidential ambition.

The GOP field is crowded, and will soon be more crowded still.

Pataki’s recently launched candidacy has yet to attract top ten status, the required entry card to a planned pre-primaries GOP candidate debate on Fox television.

But in his home state, Pataki is gaining traction.

The three-term governor heads the Republican field in the Empire State along with Florida Senator Marco Rubio, this according to a recently released opinion poll from Quinnipiac University.

Pataki and Rubio are tied at 11 percent each. Jeb Bush is at ten percent.

Polls this early are not always reliable and much in the race could change, reported the New York Observer.

But Pataki, who is at the back of the pack nationally, could gain traction and win his old state outright, the weekly surmised.

And he might do well in New Hampshire too.

Pataki has been focusing on the Granite State in the early stages of his bid and there enjoys a key advantage over the Republican pack: he, at least, is a north easterner.

He is also Irish American in addition to his Hungarian heritage.

Pataki was born in 1945, a hundred years after the outbreak of the Great Hunger in Ireland.

Fifty years after his birth, as Irish America steeled itself to mark an especially solemn anniversary, Pataki was governor of New York, a state that had been a crucial refuge for the Famine Irish.

So when it came to marking the 150th anniversary it didn't matter a whit that Pataki's name was indeed Hungarian. He had Irish on his mother Margaret's side.

And besides, the man born on the banks of the Hudson seemed ready, and more than able, to grasp the significance of an event that was bitterly remembered by some, but sidelined and largely ignored by mainstream America.

More than that, it turned out he was ready to call people to account for it.

George Pataki's rise to prominence in the Republican Party had a lot to do with his habit of bucking tradition and challenging the accepted ways of doing things.

This wrapped Pataki in an aura of freshness in the eyes of voters who gave him the nod to replace Democratic incumbent Mario Cuomo in the 1994 gubernatorial election. Voters would do so again in two subsequent elections.

For Irish Americans loyal to both parties, the arrival of Pataki brought with it a moment of uncertainty.

When it came to Ireland, Irish American Democrats and Republicans in New York tended to aim for common ground. Cuomo had drawn plaudits from both camps for his Irish positions, not least his support of the MacBride Principles campaign.

Cuomo's predecessor had been Hugh Carey, one of the “Four Horsemen.”

In the wake of both these men, Pataki, who didn't hail from a New York City borough, but from Peekskill in Westchester County, was a largely unknown quantity on Ireland and Irish issues.

This state of affairs wouldn't last for long.

Albany can be a murky place when it comes to politics and odd things can happen.

In 1995, someone in the capital's bureaucracy inserted an obscure provision into Pataki's first budget that, if implemented, would have terminated the state's MacBride Principles compliance law.

But, unlike the recent turn of events in Florida, the rescinding provision was spotted and Pataki, who had voted for the MacBride bill as a state legislator, struck it from the budget.

Support for the fair employment guidelines might have been the high point of Pataki's Irish policy but the freshman governor was now on a collision course with the British government, not over jobs in Northern Ireland, but over an historical wrong about to be writ large once again.

For years, Irish-American educators and activists had been urging inclusion of the Famine as a social studies subject in New York's public schools curriculum.

The 150th anniversary placed the issue front and center and when legislation was drawn up in Albany, Pataki, in the fall of 1996, had no problem signing the legislation into law.

He did not content himself with a moniker, however.

At the signing ceremony, Pataki accused British authorities during the Famine years of carrying out a "deliberate campaign" aimed at denying the starving Irish the food they needed to survive.

Pataki's words prompted a furious letter from then British ambassador to the United States, John Kerr.

The ambassador's broadside, and the governor's response, turned into arguably the biggest dustup between New Yorkers and the British since the Battle of Saratoga.

Kerr lambasted the governor, stating that it appeared Pataki was equating the Great Hunger with the Holocaust, confusing a natural disaster with a man-made one.

The Daily News soon got into the middle of things, accusing Kerr of being pompous.

Pataki held his fire for a time; indeed, three months were to pass before he delivered a response.

Pataki stood his ground. He had not equated the Great Famine with the Holocaust, he wrote Kerr. It was merely the case that the two would sit side by side along with slavery and genocide as human rights subjects for New York public school students.

Pataki wrote that the lofty perspective Kerr had assumed in his letter had been entirely indefensible.

Pataki again focused on the "gross inadequacy" of British relief efforts and argued that the suffering and death in Ireland were in part the result of "all too prevalent British beliefs in the inferiority of the Irish."

In outlining his view, Pataki worded his case like the lawyer he was, drawing on statements from the Famine period by British officials as evidence to back up his position.

"But although we are not obliged to take offense on behalf of our great-grandparents, we are obliged to learn from history," Pataki wrote.

"I want the truth above all to be taught. If it is, children in New York schools will learn that the Great Irish Hunger was no mere natural disaster."

Just over four months later, then British Prime Minister Tony Blair wrote a letter of his own.

British politicians during the Famine years, he acknowledged, had stood by while a defining event in the history of Ireland and Britain had turned into a massive tragedy.

Blair’s letter, read out to a Famine commemoration in County Cork, was seen in Albany as a vindication of Pataki's determined stance.

"Blair obviously is cut from better cloth than Kerr and his ilk," the Daily News sniffed in an editorial.

A couple of years later, Pataki would walk through Irish fields that had once known only the scent of death.

And from that visit, according to Jack Irwin, Pataki's liaison to the Irish American community during his gubernatorial years, would spring the Great Hunger Memorial in Lower Manhattan, opened by Pataki and President Mary McAleese in July 2002.

The memorial is a replica of a West of Ireland field, specifically one in County Mayo.

George Pataki seems to have a thing for fields, and pastures new. He lives in Garrison, in bucolic Putnam County.

And right now he's checking out the fields, (and the GOP field) in New Hampshire, working on a presidential run in a year that brings with it another standout Irish anniversary.