27/11/2014 American Chamber of Commerce Thanksgiving Lunches

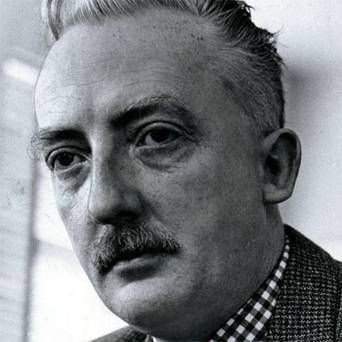

Enda Kenny

By Ray O’Hanlon

Americans citizens living in Ireland can vote in U.S. elections. Irish citizens living in the United States are barred from voting in Irish elections.

The two counties are both democracies and, fair to say, bask in strong mutual admiration.

So why the extreme dichotomy when it comes to voting?

The answer depends on who you ask.

While few Americans would ever question the right of Americans to vote no matter where in the world they live, quite a few Irish would question the right of the overseas Irish to have a vote in any form of Irish election or vote, be it Dáil, Seanad, presidential or in a referendum.

The lack of voting rights is clear evidence of this antipathy.

At the same time, just about every significant Irish political leader of the last couple of decades has been in favor of granting at least limited voting rights to the overseas Irish.

But that’s while being in opposition.

Something seems to happen to the voting rights idea after the step is made from opposition to government.

And this something spans the party divide.

Back in 1997, Fianna Fáil, then in opposition, went into a general election campaign with a clear cut promise to extend voting rights to the diaspora Irish.

The party, in its election manifesto, "People Before Politics," stated that it was "Committed to working out the arrangements to give emigrants the right to vote in Dáil, presidential and European Parliament elections, and in referendums. This can be done without amending the Constitution. Initially those who have lived abroad for up to 10 years will be eligible. Our target is to have a voting system for emigrants in place by the year 2000."

As it turned out, however, politics came before people. The voting rights pledge ended up on the cutting floor when Fianna Fáil won that year’s election.

A few years into government, the then Minister for Foreign Affairs, Brian Cowen, ruled out votes for emigrants in what was considered the most likely entity for which voting rights might be awarded – the Seanad, or Senate.

In a submission to the then Seanad sub-committee examining the future role and functions of the upper house of the Oireachtas, Cowen said that from the point of view of the Irish abroad, his view would be that the issue of votes for emigrants was “not a pressing matter.”

If the Irish abroad were to be given a voice in the Seanad, Cowen said, “it would be better to do so through the nomination of a person or persons with an awareness of emigrant issues, as proposed by the Committee on the Constitution, rather than by the election of a formal representative of the Diaspora.”

Cowen said the Emigrant Task Force – which had presented the Irish government with a report on the state of immigrant communities in the U.S. Britain and Australia – found in its consultations with Irish communities abroad that it was notable that very few people raised the question of votes for emigrants.

“Indeed, a majority of those who expressed a view agreed that, given the numbers of Irish emigrants abroad and those born abroad entitled to Irish citizenship, it would be impractical and inappropriate to give the vote to emigrants,” the minister said.

There is something of hint here of the difficulty in nailing down even limited voting rights for the overseas Irish, and it has nothing to do with reluctant politicians or even skeptical emigrants, but rather committees, sub-committees and task forces.

When governments want to pay simply lip service to an issue it is their habit to establish the likes of committees and task forces.

In the Irish case, all these above mentioned entities would be topped up by a Constitutional Convention and, most recently, the Working Group on Seanad Reform.

Back in 2013, the Constitutional Convention recommended an extension of voting rights in Irish presidential elections to the Irish overseas and in Northern Ireland.

And in recent days the Working Group came out with a recommendation that Irish citizens living abroad and in Northern Ireland should be able to vote in Seanad elections.

Promises and recommendations surround the voting issue, but in the end it is political leaders who have the power and thus far they have been most reluctant to wield it on behalf of a disenfranchised diaspora.

Taoiseach Enda Kenny is especially notable in this regard.

During the years of Fianna Fáil-led government, from 1997 until 2011, Kenny and his party Fine Gael were in favor of Seanad voting rights for the overseas Irish. Specifically, Kenny and his party backed overseas voting for three seats out of sixty in Seanad.

In outlining his party’s view of the Seanad’s future role in Irish political life, Kenny said that three senators should be elected by “overseas Irish citizens.” At one point he reiterated this view during a visit to New York.

His party’s submission to the aforementioned Seanad sub-committee was broadly in line with a 1996 consultation document – presented to the then “Rainbow” coalition government that included Fine Gael – that proposed Irish citizens living abroad for up to twenty years be entitled to elect three members to the Seanad.

Fianna Fáil - “People Before Politics” now well in the rear view mirror, at least with regard to diaspora voting - said no, though it did respond by suggesting that nomination of emigrant representatives to the senate might be possible.

Brian Cowen, still foreign minister and not yet taoiseach, argued that given the numbers of Irish emigrants abroad, and those born abroad entitled to Irish citizenship, it would be “impractical and inappropriate” to give the vote to emigrants.

Cowen’s successor at foreign affairs, Dermot Ahern, didn't move from this position. During a U.S. visit he said: "Personally I can't see that," referring to the emigrant vote idea.

For those advocating diaspora voting rights there was renewed hope when Enda Kenny led a new coalition government into power after the February, 2011 Irish general election.

Prior to the election, both Fine Gael and Labour had supported a degree of voting rights – or so it seemed.

But even before the election vote there were signs of division between the future government partners.

Labour wanted to extend voting rights to emigrants in local, general and presidential elections for up to five years after they had left Ireland, but Fine Gael's proposal at the time would have limited voting rights to only presidential elections.

Suddenly the Seanad was out of the picture.

Why this was the case would become apparent in time when Enda Kenny moved to abolish the upper house.

Before even that, and in his role as taoiseach, Kenny had, as was his right as the leader of the government, nominated eleven new members to the Seanad.

None among the eleven was drawn from overseas.

As it turned out, voters in the Republic turned back Mr. Kenny’s bid to cast the Seanad into the dustbin of history, a development which of course kept alive the idea of three senators speaking for the Irish who live in Australia and Arkansas, and everywhere else beyond Ireland’s shores.

But alive or on life support?

The Fine Gael/Labour coalition has run most of its course and there will be general election in 2016.

Clearly, there are many significant issues to be debated and battled over in the run-up to this election, not a few of them more urgent and divisive than granting voting rights to emigrants.

But the voting rights issue will be aired during the 2016 campaign.

It has never gone away.

And despite the political inertia of recent years it could be around for a long time to come.

But just there and going nowhere.