The jury in the Stardust inquests today returned a verdict of unlawful killing in the cases of each of the 48 young people who died in the fire at the Artane, Dublin nightclub 43 years ago.

According to the Irish Times, the 12-person jury reached majority verdicts in all cases, the foreman confirmed at the beginning of the hearing at the Pillar Room of the Rotunda Hospital, where the court has been sitting since April, 2023.

"They found, for the first time, that the fire that resulted in the deaths of 48 people, aged 16 to 27, started in a hot-press and was caused by an electrical fault.

"They found it was first seen outside the building between 1.20am and 1.40am, and first seen inside the ballroom between 1.35am and 1.40am.

"The time at which it was first seen inside the ballroom of the Stardust was approximately 1.35am to 1.40am.

"The height of the ceiling, the polyurethane foam in the seats and the almost 3,000 carpet tiles used to line the internal walls all contributed to the spread of the fire, they found.

"A lack of visibility because of black smoke, a lack of knowledge of the layout of the building, toxicity of the smoke and gases, the heat of the fire all contributed the speed of the spread of the fire, while failure of the emergency lighting and lack of staff preparedness contributed to the deaths.

"The jury found that at the time of the fire, exits in the Stardust Ballroom were either locked, chained, or otherwise obstructed. For this reason, the deceased were impeded in their ability to access or exit through the emergency exits.

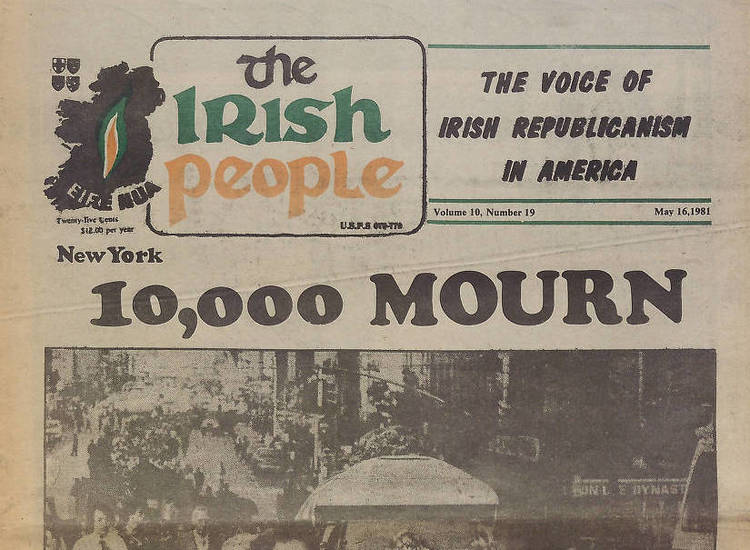

"More than 90 days of evidence and testimony from 373 witnesses was heard at the inquiry into the deaths of 48 people, aged 16 to 27, in a fire in the north Dublin ballroom in the early hours of 14th February 1981.

"Five verdicts were available — accidental, misadventure, unlawful killing, open verdict and narrative."

Later in the morning, after the flames had been extinguished, I stood in what remained of the Stardust.

I wasn't thinking of any verdict. I was just horrified by what had happened only a few hours before. I was also trying to rid my mind of what I had seen a few hours before.

The phone had erupted in the early hours. A voice at the other end of the line was instantly familiar; a colleague from the Irish Press.

He told me a taxi was on its way to take me to Dr. Steevens' Hospital. There had been a fire at the Stardust nightclub and it was bad.

"Where's the Stardust?" I asked.

As it turned out it was on the north side of the city. I was on the south side. But at this stage there were no sides to Dublin. The city had a response plan for a mass casualty event and it pulled in emergency services from the four corners of the compass.

The taxi arrived. Taxi drivers were great sources of information for reporters in those days. They were all over town all day and night. They talked to each other on radios. By the time I reached the hospital I had an idea of what happened. It was hard to fully take in.

Dr. Steevens' Hospital, a venerable medical institution dating back to the 18th century, closed in 1987. But in February, 1981 it was still operational and was home to Dublin's main burns unit. The most seriously injured from the Stardust were being taken to the hospital, which was in Kilmainham.

For several hours I stood and watched as casualties were wheeled in on gurneys. In the room where I was given to sit and interview some of the walking wounded there was also a Garda officer and a priest. I was the only reporter present. What I saw that night easily reached the dubious standard of a war zone.

As dawn broke, and after calling the Press newsroom on Burgh Quay, I made my way back along the Liffey quays. Of course this was long before the internet, cell phones and social media.

I knew a fair bit of what had happened at the disco celebrating Valentine's Day. But there was a lot more to come. The newsroom was well into its own emergency plan. I wrote my story for the first edition of the Evening Press (there were four editions of the broadsheet). I knew that an end to shift and going home wasn't an option.

Soon enough I was in a taxi and heading for Artane, the north Dublin suburb where the Stardust had been located and where a shocking number of young people had died. We were reckoning fifty. It turned out to be 48.

It would never happen today, but after waving my press card I was able to walk into the remains of the Stardust.

A photographer for the Press, Myles Byrne, had been in the newsroom when word first came through of the fire. He made his way through the night and was the only photographer on site as firemen were still carrying the dead and near dead from the smoking ruin. He took one photo that filled the back page of the Evening Press. It was a fireman carrying out a victim. Others in the picture had looks on their faces showing shock and horror.

Along with a couple of other journalists I walked, carefully, over the ash and rubble. The smell was hard to describe. Doubtless we were breathing in bad stuff. But nothing like what the kids had to inhale a few hours before. Most, we were learning, had succumbed to smoke inhalation.

Why could they not get out faster? The question was already hanging in the fetid air. The answer would be known quickly enough, but would only be given full legal standing by today's jury verdict prompted in significant part by the campaigning of victims' families over the decades.

The emergency exit doors were locked, chained shut.

I had another assignment besides describing the scene of the fire. And that was to call at homes in the area where the young had not come home after what should have been a night of fun and celebration.

I was to ask for photos of the dead.

People in shock can and experiencing sudden catastrophic loss can be unpredictable. What I do remember is kindness. In house after house I was invited in, offered tea, coffee, biscuits. And photos.

Family members wanted to talk about their lost loves ones. They wanted the lives of these kids, their short lives, to count for something in this world. The grieving were clutching. It was difficult to believe that I was somehow helping them. I felt that I was really just there to get, to take. I will never forget how those families made a gut wrenching job possible.

Over three days myself and my colleagues at the Irish Press, Evening Press and Sunday Press - like Dr. Steevens' now all passed into history - worked around the clock.

A story like this delivers a kind of adrenaline rush. You become wired, and for a time it might seem that a reporter is somehow insensitive, interested only in the "facts ma'am" and not the story giving rise to those facts.

Not true. The adrenaline is a defense mechanism. With the Stardust, and after three days, it ran out. We were exhausted, sad and shocked. We were grieving too.