On a bright June day in 1968, millions of viewers tuned in to watch the television coverage of Senator Robert F. Kennedy's funeral train making the long journey from St. Patrick's Cathedral to Arlington National Cemetery. The only guest in the CBS studio with Walter Cronkite that day was my grandfather, Sean P. Keating, a baker's son with a seventh-grade education from Kanturk, a small town in County Cork.

He had returned from his retirement in Ireland to New York with Taoiseach Jack Lynch to attend the senator's funeral. He was intercepted at Kennedy Airport by CBS staffers who requested that he appear during the broadcast. He reluctantly agreed to do so after learning that the request came directly from the Kennedy family.

During the coverage, he talked of Bobby Kennedy's interest in Irish literature and poetry, and in a rich Cork brogue he read from Thomas Davis's "Lament for the Death of Owen Roe O'Neill."

Eleven years earlier, in 1957, at the annual dinner of the Irish Institute of New York, Keating caused a stir when he was the first to publicly introduce Senator John F. Kennedy as "the next President of the United States." During his speech that evening, Jack Kennedy also read passages from Davis's masterwork.

Years later, Keating gave a copy of the poem to Bobby Kennedy, who read excerpts at the funeral of Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., only six weeks before his own death. When the call came of Bobby Kennedy's assassination, Keating had just recently attended the opening of the JFK Memorial Park in Wexford, a project which had been his singular vision This month marks the 35th anniversary of Keating's death. There are no great public works, parks, or monuments to commemorate his life, and his name is rarely mentioned in the books, articles, and exhibits celebrating Irish America. During the mid-twentieth century, however, there simply was no greater champion of "the Irish cause" than Sean P. Keating. He was an organizer, campaigner, fundraiser and front man, toastmaster, after-dinner speaker, poet, and orator. He had been an IRA rebel, a prisoner of war, and a hunger-striker. He was also a family man who operated a small insurance agency. He was a guest at the White House, and at Phoenix Park, and sat a few feet from the stage while Marilyn Monroe sang "Happy Birthday Mr. President," but he lived modestly with his family in Bellerose, Queens.

He was at once both the outside agitator, stumping for social justice and progressive causes, and theconsummate inside man, serving two New York City mayors and two U.S. presidents. He moved comfortably between the former revolutionaries back in Ireland, and the Irish Americans who had gained the ultimate prize when John F. Kennedy took the White House.

As a leader in the American Friends of Irish Neutrality, Keating campaigned tirelessly to keep Ireland out of World War II. Despite this position, Keating's dedication to his adopted country never wavered. He tried to join the army after Pearl Harbor, but was turned away because he was too old.

The forces against Irish neutrality were fierce and included U.S. Ambassador to Ireland David Grey and Francis Cardinal Spellman, who steadfastly refused to hold a Mass in support of the cause.

Eventually, Cardinal Spellman relented, and the Mass drew such a crowd that, for the first time in the history of St. Patrick's Cathedral, the congregation overflowed into the street. Years later, Keating was honored as Grand Marshal of the St. Patrick's Day Parade and knelt on the cathedral steps as he kissed Cardinal Spellman's ring.

Following World War II, as chairman of the American League for an Undivided Ireland, Keating rallied Congress in support of the Fogarty Amendment, which tied the release of Marshall Plan funds to British withdrawal from the North. Miraculously, the House passed the measure before repealing it two days later under pressure from President Truman.

Keating's commitment to Irish freedom and unification should not be confused with bigotry. He was grateful to an English military doctor who treated him while he was a prisoner and was quick to point out that many of Ireland's greatest leaders were Protestants. He was a promoter of the oppressed and an advocate for civil rights. He was shocked by the slaughter of Jews during the War and supported the creation of a Jewish state in Palestine.

In his Cork accent, he spoke out and worked street corners to raise funds for the Zionist movement. A devout Catholic in an age of anti-Semitism, Keating was later honored as man of the year by the Council of Jewish Organizations.

Keating was born in 1903 into humble surroundings. His father was from Cork, and his mother from Kerry, which he liked to say made him the product of a mixed marriage. His father was a Redmondite, a supporter of Home Rule through parliamentary action, but his older brothers argued for a revolutionary solution, and following the Easter Rising he left school and joined the Irish Volunteers at the age of thirteen. His brigade eventually became the IRA's 4th Cork Brigade and had the grim distinction of having both the first and last man executed by the British during the War of Independence.

He was arrested and beaten so badly by British troops that the governor of the Cork County Jail notified the local regiment that he would not accept any more prisoners in such a sorry condition. He was in the jail when the British set Cork City ablaze and cut the fire hoses. During the three-day voyage from Cork to the notorious internment camp in Ballykinlar in County Down, he shared one tin of biscuits with 83 fellow prisoners in the hold of an old minesweeper. The prisoners arrived at the Belfast docks to a reception of loyalists who pelted them with stones and old nuts and bolts. They were taken to Newcastle and marched handcuffed through the snow to the prison camp, which was situated on an inhospitable strip of land between mountains and sea.

During his thirteen months at Ballykinlar, Keating was involved in several aborted escape attempts and participated in three hunger strikes. After the Treaty was signed in 1921 and the war supposedly ended, the released prisoners' train was bombed by Black and Tans who had not yet withdrawn from Tipperary.

Keating returned to Cork and immediately took up with the Republican forces who opposed the Treaty. Although the Civil War officially ended in 1924, the authorities continued to harass their former adversaries, so he emigrated to New York, where he had not a single relative. He was a boarder in the Queens home of a widow who had left Kanturk for New York a decade earlier. He later married the daughter of the house, my grandmother, Una O'Doherty, and in that home, they raised my mother and her sister.

Keating worked in various jobs as a grocery clerk, car washer, and messenger. He eventually made his way into the lithography and insurance and became involved in Democratic Party politics.

When Bill O'Dwyer was elected mayor, Keating received his first city appointment and held various posts under O'Dwyer and Robert Wagner. As Wagner's assistant mayor, he was the dispenser of all city appointments and the liaison between the reform-minded mayor and the machine-style politicians who controlled the districts.

At the same time, Keating's leadership of the Irish organizations that heavily influenced city politics was legendary. At various times, Keating served as president of the County Cork association, the United Irish Counties, and the Irish Institute of New York.

When he was selected by President Kennedy for a high position in the U.S. Post Office, his appointment was temporarily held up for further background investigation because his closest friend and constant collaborator, Paul O'Dwyer, quipped to a reporter that his experience included bombing post offices during the Black and Tan War.

Although he would be the highest ranking Irishman in the U.S. government and had over 90,000 employees working under him, Keating was proudest of the fact that his department was the first to employ the handicapped, this despite heavy resistance from the Civil Service Commission. By the time he left the job five years later, there were scores of handicapped postal workers, and he was the first recipient of the Civil Service Commission's gold medal.

Sean Keating had two great dreams. One was for his country and one was for himself.

He dreamed of returning home to a free and unified Ireland. Typical of his sentiments, he told the crowd at a 50th anniversary commemoration of the Easter Rising that we must "not forget that even if the battle of the bombs and bullets has ended the fight is not yet won, nor will it be won until the tricolor floats over every corner of the island that God designed to be one, that He intended to be one and that please God will soon be one."

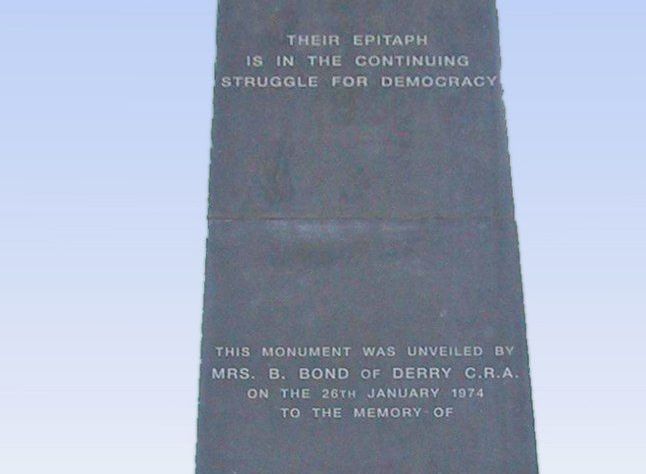

In the late 1960s, Sean Keating retired to Kanturk. He died and was buried there with full military honors in 1976, as he wished, but his dream of a united Ireland was unfulfilled.

Those of us who have never experienced the oppression of an outside occupier and never took up arms for our freedom may not share his vision, but the manner in which he fought for his life's cause should not be forgotten.

Matthew Larkin is a partner in the Syracuse, NY, law firm of Hiscock & Barclay.